The Safety Net Can Do Better for People with Poor Health and Disabilities

The economic fallout from this pandemic means that more Americans will experience poverty in the months and immediate years to come. This realization comes on the heels of the longest economic expansion in history, when many Americans escaped poverty through a combination of employment and government supports for working people. While progress on poverty may stall in the face of the impending economic downturn, policymakers can reform safety net policies to blunt the long-term effects for one particularly vulnerable group — those with disabilities and health issues.

Currently, many of our safety-net programs assume that prime-age people (age 25-54) with disabilities or health issues cannot work. This approach is misguided during good economic times, but especially harmful when the economy slows because many more people interact with safety net programs when jobs are scarce. When our policies treat people with disabilities or health issues as incapable of being productive workers, the chances that they may never work again increase — essentially trapping them in poverty and putting the social and economic benefits of employment out of reach.

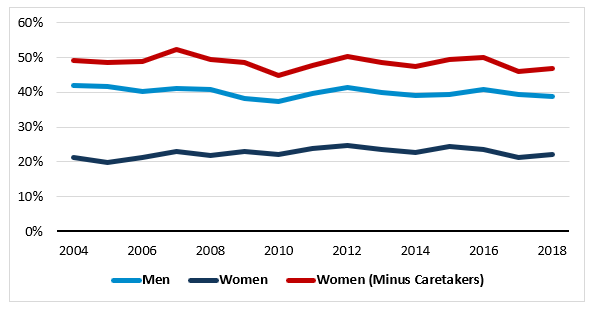

The data on the relationship between poor health, limited employment, and poverty are distressing. The vast majority of labor force nonparticipants identify disability or ill health as their main reason for not working — more than the combined share who report not working because they are in school, caring for a loved one, or because they cannot find a job. Equally concerning are data from the National Health Interview Survey, which show that 40% of prime-age men and 47% of prime-age women (excluding caretakers) who were not in the labor force in 2018 identified their health as fair or poor — a share that has remained relatively constant in good and bad economic times (Figure 1). For context, on the same survey, only 8.7% of the total prime-age population reported their health as fair or poor in 2018.

Figure 1. Share of prime-age (25-54) labor force nonparticipants with fair or poor health (NHIS, 2004–2018)

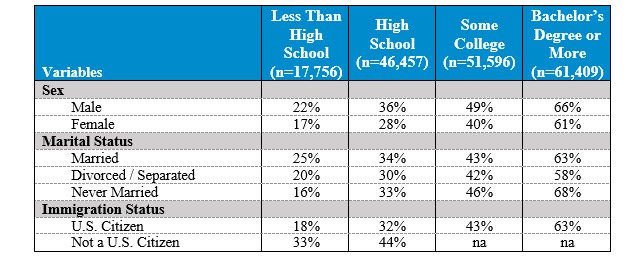

Explored from a different angle, only 32% of prime-age people who reported a disability in 2018 participated in the labor force and just over half of people who reported being in fair or poor health did the same. For these prime-age adults, not working substantially increases their chances of being poor. This is especially true when prime-age people have both a health condition and limited education. The challenges of participating in the labor force for prime-age people in poor health appear far more severe for those with limited education. In some cases, less-educated prime-aged adults with health conditions participate in the labor force at less than half the rate of their higher-educated peers (Table 1).

Table 1. Labor force participation rates of prime-age people (age 25-54) with activity-limiting conditions by educational attainment and demographics (NHIS, 2014–2018)

Government programs are supposed to offer a safety net to people who cannot work due to a disability or health issue; but in reality, government programs often encourage idleness and contribute to the alarming statistics above. Prime-age people have to prove a permanent work-limiting disability to receive assistance from Social Security Disability Insurance or Supplemental Security Income, which makes them less likely to search for work while waiting for a decision. In the meantime, they can access benefits from other safety net programs, but these programs largely exclude them from employment-related services that are available to (and sometimes required of) healthy benefit recipients.

While it is true that some work conditions are not compatible for people with health conditions or disabilities, changes in the economy are creating more viable employment opportunities for many people. Similarly, health advances are increasing the effectiveness of treatments and accommodations for people who face poor health and disabilities. Our safety net programs can do more to help low-income people access these advancements and overcome their health challenges so that they can successfully reconnect to the labor market.

In a new report, I identify four broad areas of reform aimed at better serving people with disabilities and health issues. These include: (1) public health and social welfare policies aimed at helping people become healthy enough to work; (2) private sector efforts to improve jobs and job conditions that support good health; (3) government safety net programs focused on helping prime-age benefit recipients gain employment; and (4) supportive employment for people with disabilities and health issues.

The coronavirus pandemic has reminded us all of the important relationship between good health and a strong, functioning economy. Now more than ever, we need policies that create an environment for higher levels of labor force participation among prime-age people so that, in the months and years following this crisis, we can ensure that good health and active participation in the labor force is a reality for low-income Americans with disabilities and health issues.

Angela Rachidi is the Rowe Scholar in poverty studies at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI).