A Tent City Challenges Developers in the Old Home of the Braves

Atlanta’s old major league ballpark may be empty, but the sidewalk outside is buzzing.

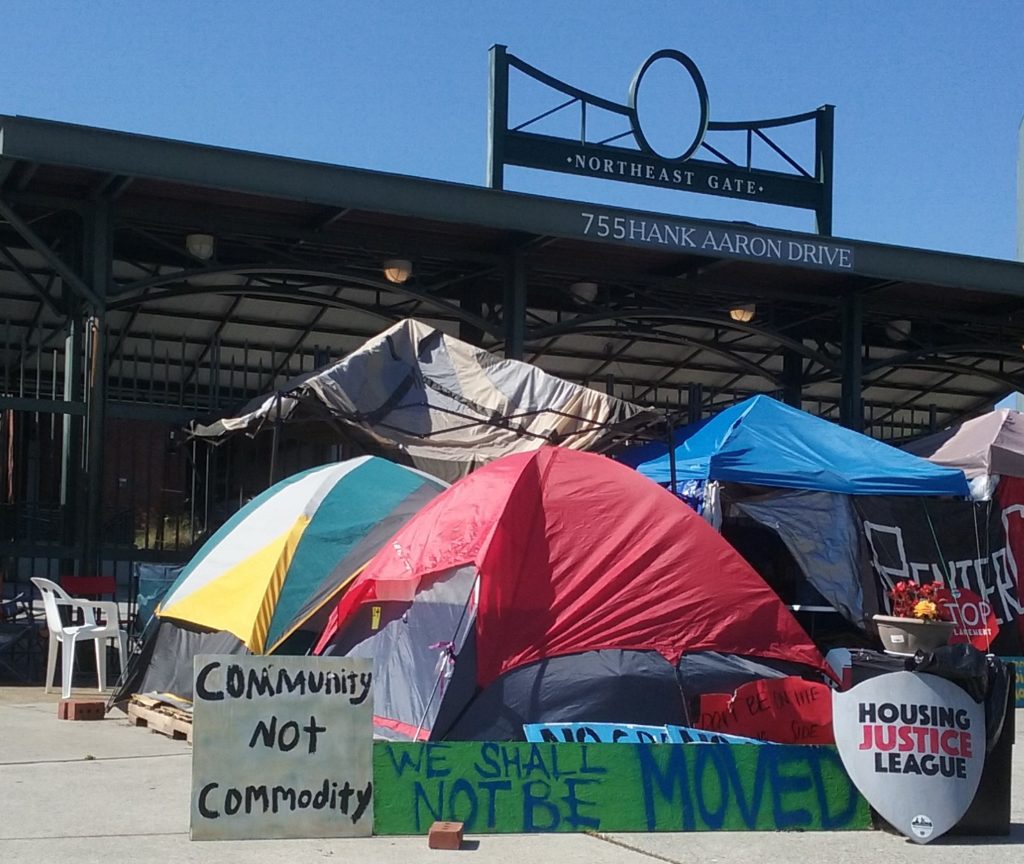

Tents fill the plaza outside the northeast gate of Turner Field, the home of the Braves from 1997 through 2016. The stadium is now owned by Georgia State University, which wants to knock down much of the structure and transform the rest into a football field. The people who have been camping in those tents for more than a month now are trying to make sure homes in the surrounding neighborhood aren’t the next casualties.

The month-old encampment, dubbed #tentcityATL, is aimed at convincing Georgia State to sign a binding agreement that will protect their low-income communities from a wave of gentrification and displacement that’s already transforming other nearby neighborhoods. Residents who have banded together under the banner of the Turner Field Community Benefits Coalition say they want a voice in the vision being laid out for their neighborhoods. Their insistence is fueled by more than a half-century of disappointment with other redevelopment plans and promises, which led to the carving up of what had been middle-class, largely integrated communities in the years before the second world war.

“This was an Austin’s grocery store when I was a little girl,” said Clemmi Jenkins, a lifelong resident of the Peoplestown neighborhood, pointing to the concourse outside the now-empty ballpark. “It was as big as any Kroger. There used to be a library right there, a movie theater, an ice-cream parlor – all of that was here. But with the redevelopment, it was gone.”

Clemmi Jenkins

Before World War II, the neighborhoods around Turner Field were home to a mixture of blue-collar and middle-class families. The population included both African-Americans and whites, drawing heavily from Jewish and Greek immigrant communities. One of Atlanta’s biggest hospitals was founded in Summerhill, north of where the ballpark now stands.

But starting in the 1950s, many of the area’s white residents moved to neighborhoods further north or to the growing suburbs. Then came the interstates, which quartered Atlanta from north to south and east to west. Thousands of homes were torn down, largely cutting off Peoplestown from the Mechanicsville and Pittsburgh neighborhoods to the west, and Summerhill from downtown to the north.

Then in the mid-1960s, Atlanta convinced the Braves to move to town from Milwaukee, promising the team a new stadium on 47 acres just south of the massive interchange where the freeways cross. Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium opened in 1966. Three decades later, Atlanta built a massive new arena next door for the 1996 Olympic Games; when the games left town, the old ballpark was torn down and replaced with a parking lot for the new one, which was reconfigured into Turner Field.

Each time, the surrounding residents were promised the ballpark would bring new life and prosperity to their streets. Each time, they were disappointed. The Braves kicked in a portion of the team’s parking-lot revenues to community organizations, and some new homes went up in Summerhill around the time of the Olympics—but the rest of the area languished.

The population fell from about 32,000 in 1940 to fewer than 6,000 by 2011. Pre-war storefronts along Georgia Avenue stood empty but for a Chinese restaurant and a liquor store. Turner Field was surrounded largely by vacant lots, which filled with cars at $10 or $20 a pop on the 81 days a year the Braves were in town.

“You had a severe lack of investment in our community,” said Chris Lemons, president of the Peoplestown Neighborhood Association and a former member of the Turner Field coalition.

“Then, from a perception standpoint, there seemed to be a lot of negative stereotypes around downtown and that area … You never had anybody coming in trying to open up a restaurant or start businesses once the stadium got closed. That’s the sad thing about it. It could have been much more than just a big parking lot.”

When the Braves announced in 2014 that they would be decamping up Interstate 75 for the suburbs of Cobb County, the neighborhoods around the ballpark heard the same kind of promises. This time, they want something in writing.

The coalition’s members are elected from the surrounding neighborhoods, and it conducted a community survey to help shape its demands. Its members want Georgia State and the private developer it’s working with to include affordable housing in the area, as well as support for job training and college preparation for students in neighborhood schools.

They want businesses like supermarkets to move back into the community, and improvements to basic infrastructure like streets and storm water drainage. They also want some sort of help to keep people – many of them retired and on fixed incomes – in their homes as speculators move in and property values go up. Their campsite has drawn support from several of the candidates who will be on the ballot when Atlanta votes for a new mayor in November. The area’s congressman, civil rights legend John Lewis, also has dropped by to show support.

The tents are largely occupied by community activists and students from several nearby colleges, including Georgia State. Neighborhood residents are on hand to answer questions. Drivers occasionally honk or give a thumbs-up as they roll through. Other times, they yell insults, says longtime Peoplestown resident Lou Braxton, who’s minding the tents one warm Tuesday: “Stuff like ‘Get a job,’ “ she said. “They don’t know whether you have a job or not … that’s just crazy.”

And every now and then, they get someone who wants to argue, like a man who took issue with a sign reading “This land is our land.”

“It ain’t your land. You ain’t ever paid taxes on it — not on this property,” says the 60-ish white man wearing a “Let’s Roll” baseball cap emblazoned with an American flag. He says he grew up a couple miles away, but he won’t give his name, and he’s not much interested in what the campers have to say.

“I’m a graduate of Georgia State. That is the best thing that’s ever happened to this community,” the man says. “It went to hell in a handbasket 40 years ago … now y’all are out here protesting the best thing that’s ever happened to the south side of Atlanta.”

The weather hasn’t treated them kindly, either. Late April and early May brought an unseasonable chill and heavy thunderstorms that left the campers scrambling to stay dry.

“It’s a mess,” said Athri Ranganathan, an activist with the Housing Justice League. “We’re watching to make sure these zip lines are holding tight when the storms come through, and the water isn’t weighing down the tents.” But he said the campers have sleeping bags, mattresses and pillows, and they’re prepared to hold on “as long as it takes.”

But the coalition also has suffered some high-profile defections. Lemons said his neighborhood association left amid a dispute over tactics and goals, as well as disagreements over leadership. Other people split from the coalition when they saw the possibility of greater profit from a deal with developers, he said. Now, associations from Peoplestown, Summerhill, Mechanicsville, and another neighborhood – the more affluent Grant Park, about half a mile east of the stadium – are in talks with the university on their own, he said.

Some of the tents outside Turner Field

“We still wanted to make sure that we spoke up for our community,” he said. “But as far as being in the coalition was concerned, we didn’t feel that would be best at this point.”

In March, GSU President Mark Becker called the group “a self-interested group of people that have their own personal agendas” and suggested its members were out “to extort money” from the university. GSU, which bought the 70-acre stadium site for $30 million, has more than 30,000 students at its downtown campus. It has been a major player in the revitalization of Atlanta’s urban core, buying and renovating old buildings and erecting several new ones, including thousands of units of student housing. It says it’s working with the city and community organizations to help shape the redevelopment to the best interests of everyone involved—but says it’s barred by law from transferring money to the neighborhoods.

In late April, the university and its private developer partners announced they had reached a deal with the neighborhood associations that had split off from the Turner Field coalition. That agreement calls for Georgia State to make educational, health, and legal aid programs available to the community and use minority contractors whenever possible; a separate agreement with the developers pledges to work on drainage and transportation issues, help residents get jobs with the project, and create “a vibrant public realm that encourages interaction and promotes activity.”

The campers immediately denounced the announcement as “fake news,” saying the agreement had been presented to them less than an hour before the university put out a press release hailing a deal. And though the Peoplestown Neighborhood Association was one of the groups named in the university statement, Lemons says his organization has not signed onto the proposal.

However, the Turner Field coalition and the school are now in talks over the proposal, with city officials acting as intermediaries, said Maya Dillard Smith, a lawyer and political strategist who is advising the coalition. The developers have begun sharing more details of their plans, and Dillard Smith said the residents have more of a seat at the table than before.

But the plan presented in April “does not have any metrics that would allow for accountability,” she said.

“There’s no metric of the amount of investment for the neighborhoods that would be impacted by this project,” Dillard Smith said. “There are no metrics for how many jobs will be created. There are no metrics for exactly how many units of housing will be created, how many square feet of commercial space will be available, how much of that housing will be affordable.”

And while the proposal calls for 10 percent of non-student housing built to be affordable, Dillard Smith said it defines that as something people making 80 percent of the area’s median income can afford – “which means someone who’s at roughly $60,000 or more. That’s not really attending to the needs of this community, where the average income is about $25,000.”

GSU spokeswoman Andrea Jones said there was “continued conversation around our plan,” but provided no details. In the meantime, the tent city campsite remains: Jones said campus police are patrolling the property, but there are no plans to force the protesters to leave—and residents say they’re determined to secure the assurances they want.

“All I’m saying to Georgia State is, work with us,” Jenkins said. “We’re not mean. We aren’t crazy … We need to hear from everybody involved.”

Matt Smith is an Atlanta-based journalist who covers a variety of issues, including science, medicine, juvenile justice and related public policy issues. His work has appeared in outlets like CNN, Vice News, WebMD and Youth Today.