Misunderstanding Persistent Poverty and Employment

It may seem simple, but the role employment plays in explaining poverty in America is frequently misunderstood, especially when it comes to understanding why people might be poor for many years. It is generally accepted that having a job is a good way to avoid poverty, but policy debates too often focus on the “working poor,” meaning those who maintain consistent employment but are still in poverty. As it turns out, being stuck in poverty while maintaining steady employment is extremely rare.

The general public seems to make the same mistake. In a 2016 public poll conducted by the Los Angeles Times and the American Enterprise Institute, 60% of respondents believed that most poor people have been that way for a long time, and the majority agreed with the claim that most people in poverty hold steady jobs. Neither of these is true.

The truth is that being poor year after year is uncommon in America, and a steady job almost always lifts households out of poverty. Persistent, or long-term poverty, is nearly nonexistent when someone in the household works steadily. This suggests that focusing exclusively on the “working poor” as many politicians do, is misguided. Instead, policies aimed at getting more people to work consistently will better reduce poverty than perhaps anything else.

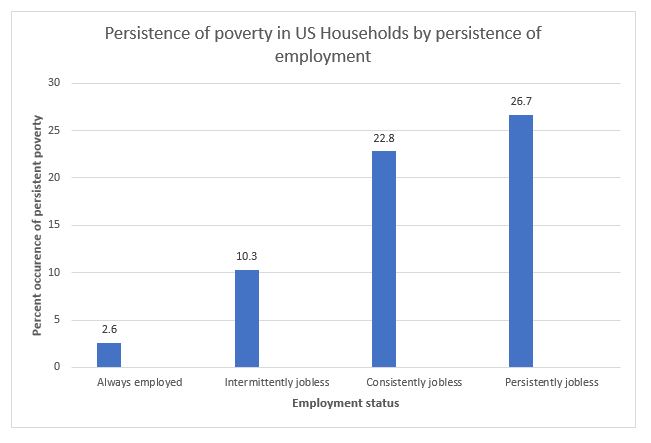

Some people are surprised that full-time work is so strongly linked to poverty alleviation, and that working consistently almost eliminates long-term poverty entirely. But the data are uncontroversial and unambiguous. In a 2015 report, the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed that 95.4% of people who worked for at least half the year did not fit the official definition of being poor. A recent working paper from American Enterprise Institute confirms these general findings, showing that only 2.6% of households with a consistently working adult were persistently poor (defined as being in poverty for more than 27 of 36 months) even during the worst years of the recession. The poverty rate was ten times higher for households with a persistently jobless person, meaning without a job for most of a three-year period.

Source: Persistent Joblessness and Poverty in the United States, Angela Rachidi, American Enterprise Institute

Annual poverty rates are sometimes used in ways that add to these misperceptions. Presented as the share of Americans in poverty, the official poverty rate leads many to wrongly assume that the same people are in poverty from year to year. Opinion pieces that use annual rates to suggest that Americans “languish” in poverty add to this mistaken belief, while estimates show that fewer than four percent of people experience poverty for three years straight or more.

When considering the misperceptions that exist about long-term poverty and employment, it’s no surprise that policies such as increasing the minimum wage are so popular. But these types of policies miss the vast majority of poor adults who do not work at all, and in some cases risk making full-time employment even harder for them.

Recognizing this reality, government policies should instead focus more on what can be done to help increase steady employment. Emphasizing work in safety-net programs through a combination of work requirements and employment services, similar to what has already been proposed in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid, would better help the long-term poor. And government policies that help keep workers connected to the labor market, such as paid parental leave and child care assistance, would help limit the share of people who spend extended periods of time jobless not by choice.

Beyond that, our communities and civic society must reinforce basic norms around work and family life. As Michael Strain of the American Enterprise Institute wrote last year, “For the working class, as for all Americans, the sense of duty [to work] rests on cultural norms—norms that have been eroding and need to be reinvigorated.”

Tackling poverty in America is made especially challenging when misinformation pervades public discourse. Incorrect views and misleading representations of the relationship between poverty and employment will only result in misguided policy solutions that could do more harm than good. As political scientists Brian Southwell, Emily Thorson, and Laura Sheble warned in an American Scientist article earlier this year, “misinformation is concerning because of its potential to unduly influence attitudes and behavior, leading people to think and act differently than they would if they were correctly informed.” Considering that anti-poverty policies cost this country billions of dollars each year, making sure that programs target the right problem is critical.

Angela Rachidi is a research fellow in poverty studies at the American Enterprise Institute.