A Medicaid Work Requirement Will Threaten Coverage for Many People Who Need Health Care

The Trump Administration is launching a new campaign to cut Medicaid, after the failure of last year’s attempt with congressional Republicans to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and make other cuts to health insurance. This time, the Administration is encouraging states to impose work requirements in the program, which wouldn’t actually help beneficiaries work but would make it much harder for people to qualify for Medicaid and stay covered.

The Administration announced earlier this month that states may block some low-income adults from getting Medicaid coverage if they’re not working or participating in work-related activities. Prior administrations have consistently rejected this idea because it’s inconsistent with Medicaid’s core mission of providing comprehensive health coverage to low-income people so they can get needed health services.

Medicaid is and should be a health program, with decisions made first and foremost based on what supports better health outcomes. The health consequences of losing coverage, or interruptions in coverage, are just too severe to take away people’s insurance as a punishment for not working or not being able to find a job. That’s why physicians have consistently been strong opponents of Medicaid work requirements. The AMA, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the professional organizations of ob/gyns and psychiatrists are all opposed. So are major patient groups, behavioral health providers, and advocates for people with disabilities.

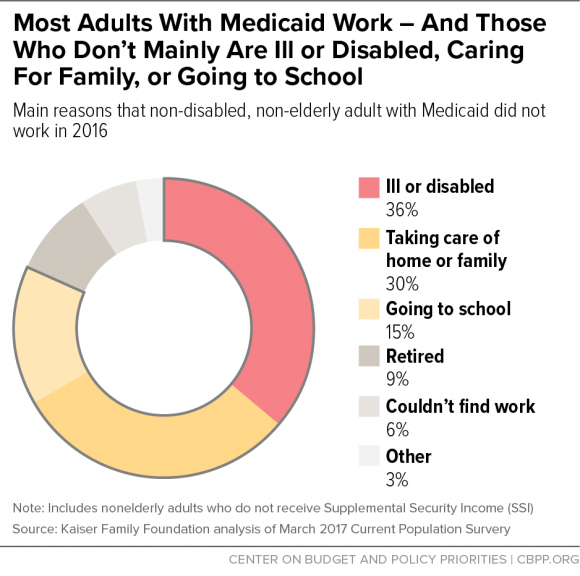

Moreover, most Medicaid beneficiaries who can work are already working. Nearly 8 in 10 non-disabled adults with Medicaid coverage live in working families, and most are working themselves. Most who aren’t working have health conditions that prevent them from working, are taking care of their home or family (often caring for children or other family members who are ill or have a disability), or are in school, as the graph shows.

Medicaid work requirements are also ill-conceived: they will make it harder for nearly all non-elderly adult enrollees to get coverage, in an effort to influence the behavior of a small minority of that group. Work requirements could also make it harder for some adults to succeed in the labor market by eliminating their health coverage. In studies of adults in Ohio and Michigan, majorities said that gaining Medicaid coverage helped them look for work or stay employed. Losing coverage — and, with it, access to mental health treatment, medication to manage chronic conditions, or other important care — could have the perverse result of impeding future employment. This would be particularly problematic for people with substance-use disorders such as opioid addiction who rely on Medicaid for access to needed treatment but may have trouble meeting work requirements. Despite the evidence that work requirements would harm beneficiaries, the Administration approved Kentucky’s request this month to make work or work-related activities a requirement for Medicaid eligibility.

Kentucky was one of the rousing successes of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion; its uninsured rate among low-income adults plummeted from 40 percent in 2013 (the year before the expansion took effect) to 7.4 percent in 2016. Growing evidence shows that as a result, low-income Kentuckians are less likely to skip medication due to cost, less likely to have trouble paying medical bills, and likelier to get regular care for chronic conditions.

The state’s planned changes will jeopardize this progress by making it harder for people to get and maintain coverage, increasing paperwork, and reducing enrollees’ access to care. The state itself projects that its proposals will cut adult Medicaid enrollment by 15 percent by the fifth year.

If states really want to promote work among Medicaid beneficiaries, Washington State shows one way how. The state has asked federal permission to expand services that help beneficiaries with significant physical or behavioral health conditions to get housing and jobs. People who’ve been in institutions or homeless for long periods often need special supports to manage their health and the responsibilities of living on their own, such as help finding housing that’s safe and affordable, finding community social services, and understanding their rights and responsibilities as tenants. Washington State’s proposal will support work by giving Medicaid beneficiaries more tools to secure employment.

For millions of low-income people, Medicaid coverage means access to health coverage for a sick child or a family member with a chronic illness, or long-term care for an elderly parent. It means significantly improved financial well-being, and studies show that kids covered by the program do better (and go farther) in school. It means having a regular doctor and getting care when you need it, with comparable access to care as private coverage. Moreover, Medicaid costs less per beneficiary than private insurance, and its costs have been growing more slowly than private employer coverage.

During the debate over ACA repeal, the White House stated that, “We don’t want anyone who currently has insurance to not have insurance.” The Administration should stand by this commitment by supporting state Medicaid proposals that would enhance coverage and improve the delivery of care and rejecting proposals that would force people off the program or make it harder for them to get health care.

Hannah Katch is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.