In North Carolina, the Racial Justice Act Goes Back To Court

The story is co-published with The Assembly as part of a new content partnership.

The same year a Johnston County jury recommended a death sentence for Hasson Jamaal Bacote, the North Carolina General Assembly passed a law that could save his life.

In August 2009, a Democratic majority in the General Assembly passed and Gov. Bev Perdue signed into law the Racial Justice Act, allowing those sentenced to execution the chance to instead spend life in prison if they could prove race played a significant role in their case. The law resulted from years of work and ongoing debates about racial disparities in the criminal justice system, particularly in decisions to impose the death penalty.

A year after his conviction for first-degree murder, Bacote filed a claim under the Racial Justice Act. Virtually all death-row inmates did the same. The law allows inmates to file a claim and a judge can hold an evidentiary hearing to decide whether the claim has merit. And while the judge can commute a sentence to life in prison without the possibility of parole under the act, that’s the only option; it’s not meant to challenge a conviction.

It’s taken Bacote, now 37, nearly 14 years to have his claim heard.

Cumberland Superior Court Judge Gregory Weeks held the first evidentiary hearings for four defendants—Marcus Robinson, Quintel Augustine, Tilmon Golphin, and Christina Walters—in 2012. He commuted all four defendants’ sentences to life, but the state Supreme Court overturned Weeks’ ruling on procedural grounds and sent the case back to a court in Cumberland County.

In 2012 file photo, Marcus Robinson listens as a superior court judge rules that racial bias played a role in his trial and sentencing. (Shawn Rocco/The News & Observer via AP) Credit: AP

At the same time, prosecutors openly opposed the law and lobbied the Republican-controlled General Assembly to get rid of it. State legislators had already narrowed the scope of the law in 2012 and fully repealed it in 2013. Defendants in two Iredell County death penalty cases went to the state Supreme Court, arguing the law’s repeal doesn’t keep their pending claims from being heard.

In 2020, the court agreed, meaning that the more than 100 pending Racial Justice Act claims could go forward. In separate opinions, the court also ruled that the four Cumberland County defendants had to be removed from death row and resentenced to life.

The year after that decision, Superior Court Judge Wayland Sermons Jr., who is presiding over Bacote’s case, ordered prosecutors to produce statewide data on capital murder cases going back to 1980, including jury selection notes. That produced more than 680,000 pages of discovery.

Now Bacote’s legal team, which includes attorneys from the ACLU Capital Punishment Project, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and the Center for Death Penalty Litigation, will use that data and other evidence to try to convince Sermons that racism permeated not only Bacote’s case, but every capital murder case in North Carolina. The hearing starts on February 26 and is expected to last three weeks.

This is the first Racial Justice Act evidentiary hearing in more than a decade, and as the lead case, Sermons’ ruling would set a tone for how every other pending Racial Justice Act claim could be decided.

Ultimately, the case could either restart the death penalty or end it for good, said Noel Nickle, executive director of the N.C. Coalition for Alternatives to the Death Penalty.

“I think all eyes are on this case,” she said.

. . .

Bacote was 20 when police in Selma, N.C. arrested him for the murder of Anthony Surles, a student at Smithfield Selma High School.

Surles died February 17, 2007, the day after he was shot.

Johnston County prosecutor Lauren Tally told jurors at Bacote’s trial that Surles had gone to his brother Carlos’s house, a single-wide trailer on Hunting Drive. Carlos wasn’t there, but his girlfriend, Terra Manning, was, along with her two young children, her cousin, and two of Surles’ teenage cousins. Manning and her cousin were getting the children ready for bed while Surles and his cousins played video games.

Someone knocked on the door, the prosecution said, and when Manning went to answer, a tall man wearing gloves and holding a handgun entered, along with another man holding a long gun. Police later identified the first man as Jeffrey Evans and the second as Bacote.

Bacote pointed his gun at the three young men on the couch, and both men demanded money. When Surles bolted toward the front door, Bacote fired one shot at him, the prosecution said. Surles was later found two trailer lots away with a gunshot wound to the chest.

At trial, a jury convicted Bacote of first-degree murder, and Superior Court Judge Thomas Lock sentenced him to death. Bacote’s attorneys said there was never any evidence that Bacote planned to shoot Surles, and that he didn’t even realize the young man had been injured until his body was found later.

Prosecutors argued that Bacote was guilty of first-degree murder simply because Surles died during a robbery, known in legal terms as the felony murder rule. (Bacote is one of 11 people sent to death row under the felony murder rule since 1985, nine of whom are Black, and he is the only one convicted of first-degree murder in a case where prosecutors didn’t also pursue premeditation and deliberation.)

Bacote’s attorneys also said other factors weren’t considered, including the immense amount of trauma Bacote experienced at a young age. His parents abandoned him, he saw his aunt die, and he was physically and sexually abused in the foster care system, they said.

Evans was convicted of second-degree murder and served nearly 19 years in prison. He was released in 2022. A third man, Antwain Groves, was convicted of accessory after the fact to second-degree murder and served nearly eight years in prison. He was released in 2014.

Bacote’s attorneys allege that he never had a chance in the criminal justice system. He was doomed from the moment Selma police arrested him, they say.

. . .

Johnston had its beginnings as a small, rural county just southeast of Raleigh whose economy was rooted in slavery through the 19th century. Into the next century, Black people faced brutal racism and violence, according to a report that historian Crystal Sanders prepared for Bacote’s hearing. Sanders writes that four Black people were lynched between 1884 and 1914.

The last was Jim Wilson, a 25-year-old Black man accused of killing a white woman. On the morning of January 27, 1914, a mob of 500 people pulled Wilson out of the Selma jail to beat and shoot him, Sanders said.

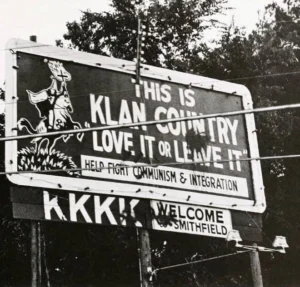

The Ku Klux Klan operated in Johnston County as early as 1926, and for decades, two billboards welcoming visitors announced the white supremacist group’s presence, according to Sanders’ report. In fact, the entrance to Smithfield from the west had a sign that declared,“This is Klan Country. Join and Support the United Klans of America, Inc. Help Fight Communism and Integration.” After civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was killed in 1968, Klan members marched through Benson, brandishing weapons, the report said.

Bacote’s attorneys argue in his Racial Justice Act claim that Johnston County’s history of racism tarnished any chance that Bacote had at getting a fair trial there. A study by two Michigan State University law professors outlined statistics statewide and in the county showing prosecutors struck potential Black jurors at higher rates than white potential jurors. The lead prosecutor in Bacote’s case, Gregory Butler, struck eligible Black people from the jury pool at 10 times the rate of non-Black people in four cases he tried, including Bacote’s, according to the Michigan State University study.

But that’s not the only evidence, Bacote’s attorneys say. They culled prosecutor notes from around the state and found a pattern of prosecutors referencing the race of Black potential jurors or making racist statements. In the 1993 case of State v. Rayford Burke in Iredell County, prosecutors described a white juror as having a “good address” and then said “affluent people who have blacks living behind them.”

In the 1992 case of State v. Herbert Barton, a Robeson County prosecutor said a white juror lived in the “Black section.”

During his closing arguments in a 2001 murder trial, Butler told the jury that “He who hunts with the pack is responsible for the kill,” and that the three Black defendants in the case “stalked their prey, caught, and dragged it away” like “predators of the African plain.” He also compared the defendants to wild dogs and hyenas.

Sign at the entrance to Smithfield. (Photo via Digital NC)

For the past two years, Bacote’s attorneys have pored over hundreds of thousands of pages prosecutors turned over—jury questionnaires, prosecutor notes, and other documents from more than 200 death penalty cases from around the state.

Cassandra Stubbs, one of Bacote’s attorneys and the director of the ACLU Capital Punishment Project, said Bacote’s hearing will be the first time that such evidence will be presented in a court of law.

Seven expert witnesses are expected to testify, including Bryan Stevenson, a noted criminal defense attorney whose story was behind the movie Just Mercy.

Stubbs said they will also present the Michigan State University study and other research showing that prosecutors both in Johnston County and across North Carolina discriminated against potential Black jurors. All of it, Stubbs said, indicates a pattern of statewide racial discrimination in death penalty cases.

Prosecutors with the N.C. Attorney General are fighting back to keep those studies out of court. They have always been opposed to Bacote’s claims, arguing that the Racial Justice Act is unfair and that the Michigan State University study doesn’t represent adequate evidence. They have filed motions seeking to keep the study from being presented and to prevent defense experts from testifying.

But on January 5, state prosecutors filed a motion seeking to dismiss Bacote’s jury discrimination claims, citing a recent state Supreme Court ruling in another case, State v. Russell William Tucker. Tucker is a death-row inmate who claimed Forsyth County prosecutors used a cheat sheet to illegally strike every Black potential juror from his trial, leaving him with an all-white jury. His attorneys also cited the Michigan State University study. In December, the state Supreme Court rejected his claims, saying they should have been raised in earlier appeals, and called the Michigan State University study “fatally flawed.”

Prosecutors said the ruling in Tucker means that Bacote’s attorneys can’t use it and holding an evidentiary hearing would be a “waste of judicial resources” because Bacote’s other evidence isn’t sufficient to prove racial discrimination.

Judge Sermons denied that motion, and prosecutors asked the state Supreme Court to temporarily stop the evidentiary hearing so it can review Sermons’ decision. The court has denied the request to stop the hearing but has not decided on whether to review Sermons’ ruling.

The N.C. Conference of District Attorneys filed a brief with the state Supreme Court, arguing that Sermons clearly erred in his decision and that he should have denied Bacote’s Racial Justice Act claim without a hearing.

“Having a definitive ruling from this Court concerning the use of the MSU Study to support motions for appropriate relief based on the [Racial Justice Act] would save considerable judicial resources that otherwise would be utilized for unnecessary evidentiary hearings,” Robert Montgomery, who is representing the conference, wrote in his brief, noting that more than 100 pending claims have yet to be resolved.

Bacote’s attorneys say the legal standard for Tucker’s case is vastly different than for Bacote’s. Tucker was arguing that prosecutors had violated the U.S. Supreme Court case Batson v. Kentucky, which prohibited attorneys from using race in jury selection. Bacote is making his jury discrimination claims under the state Racial Justice Act, his attorneys argue.

Nickle, with the N.C. Coalition for Alternatives to the Death Penalty, said litigation over the Racial Justice Act is one of the reasons North Carolina hasn’t had an execution in nearly 18 years. She said the death penalty is built on a foundation of systemic racism in North Carolina, and Bacote’s case shows that.

“If the courts cannot align with that finding that is so clear, then that’s very troubling about the course our courts might take not just about the death penalty but about the broader criminal punishment issues,” she said.

Michael Hewlett is a staff reporter at The Assembly. He was previously the legal affairs reporter at the Winston-Salem Journal.