How a Working Family Credit Could Support Work and Marriage to Reduce Poverty

People often say that poverty in the US is a policy decision, suggesting that the government could eliminate poverty if it simply transferred enough money to poor families. It was this belief that partly motivated the push for a permanent expansion to the Child Tax Credit (CTC) in 2021. The CTC expansion not only would have increased the amount of support families received, it also would have made the CTC fully refundable, meaning the credit would be available to households without any employment for the entire year. But fighting poverty is far more difficult than simply giving families money, and such an approach ignores two crucial components – employment and marriage. Policies that focus on these factors would give families a much better chance to escape poverty permanently than a fully refundable CTC.

Refundable tax credits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the CTC are important components of the social safety net for low-income families in the US. The EITC and the CTC (prior to the temporary expansion) already decreased the child poverty rate by 5 percentage points in 2020, more than any other safety-net program. Moreover, research shows that the EITC increases employment because of its connection to work and consequently, helps contribute to higher material well-being among single mother families.

Expanding the CTC to nonworking families risks some of this progress by undermining employment. Furthermore, even the current system has flaws. The EITC still penalizes marriage by offering a larger benefit to many working parents when they stay unmarried rather than decide to marry. Policies like these undermine employment and marriage and make it harder for families to escape poverty and achieve upward mobility.

In a new report for the American Enterprise Institute, I introduce a better alternative. I propose combining the EITC and CTC into a Working Family Credit (WFC) that would both strengthen the work incentives of the existing system and reduce marriage penalties. In my view, a combined credit offers several advantages over the current system, including simplifying the administration of child-related tax benefits and aligning the rules for the EITC and CTC. Perhaps even more crucially, however, the WFC would align the federal government’s anti-poverty approach to incentivize two of the most important tools for helping families permanently rise out of poverty – employment and marriage.

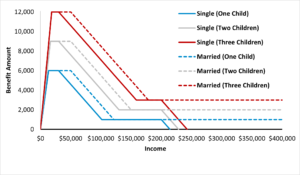

The WFC would provide a maximum refundable tax credit of $6,000, $9,000, and $12,000 for families with one, two and three children, respectively (Figure 1). To incentivize employment, this credit phases in quickly starting with the first dollar of earnings. It starts phasing out at $30,000 for single parent families and $50,000 for married families until reaching a floor of $1,000, $2,000, and $3,000. The credit would not phase out completely until very high income levels. The only other families excluded are those with zero work-related earnings for the entire year. These families need much more than a government check, and federal policy should focus on providing them job training, education, and other services through the existing social services infrastructure.

Figure 1: Working Family Credit Parameters

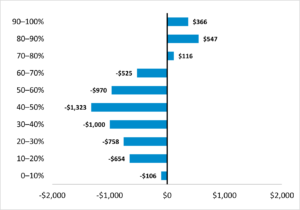

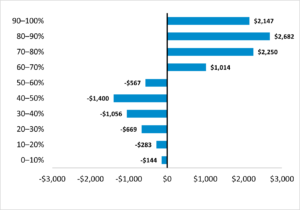

Without considering any possible behavioral changes such as to employment or marriage, families with incomes between the 0-60th percentiles would see a decrease in average taxes through the WFC. Working married- and single-parent families between the 30-50th income percentiles would see the largest reduction in taxes (Figure 2). For those without any federal income tax liability, this difference would come as a lump sum payment at tax time.

Figure 2: Average Tax Change in 2022 by Income Decile: Current Tax Credits vs. Working Family Credit

- Married Filing Jointly

2. Single Parent

A policy focus on increasing employment and encouraging marriage can lead to uncomfortable conversations about the root causes of poverty. However, the data are clear—low levels of employment and unmarried parenthood are strongly associated with higher poverty rates and policies that improve those factors would benefit children. Too often, people misinterpret policy intentions designed to address these factors as blaming people for their challenges. However, when viewed another way, existing federal policies that undermine employment and marriage harm low-income families by denying them opportunity. Policymakers should reaffirm the reality that employment and marriage help low-income families to move up the income ladder. Moving towards a consolidated child tax credit such as the WFC could help realize this goal.

Angela Rachidi is a senior fellow and the Rowe Scholar in poverty studies at the American Enterprise Institute