Advancing Racial Equity Through the Tax Code

The federal tax code doesn’t explicitly benefit one race over another, but it directly affects the income and wealth of virtually every household, it raises revenues that support critical programs and investments to expand economic opportunity, and it helps shape markets and behavior. It can therefore be a powerful tool to advance racial equity. Indeed, the current tax code narrows racial disparities overall in some ways, but other aspects of the tax code reinforces them. Here are three ways the tax code and how it’s administered affect these disparities, along with three ways to reform it to far better harness its power to advance equity.

First, some background. Historical racism and continuing racial prejudice and discrimination have helped shape factors — such as income, wealth, and consumption — that determine households’ tax liability. Racial barriers to economic opportunity, such as labor market discrimination and disinvestment in low-income communities’ infrastructure, have helped create deeply unequal distributions of wealth and income with households of color disproportionally concentrated at the bottom while white households are heavily overrepresented at the top. Further, historical racism has directly influenced decisions that have shaped the tax code itself.

So how can the tax code and its administration affect racial disparities? And how can tax reforms can help advance racial equity?

First, the tax code raises revenues progressively, meaning high-income and wealthy people pay a greater share of their incomes in taxes than lower-income people. This progressivity modestly reduces income and wealth gaps, and hence racial disparities. The revenues it raises support investments that can advance racial equity – think economic security programs in areas such as health and housing and crucial infrastructure investments in neglected low-income communities of color.

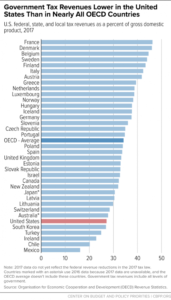

But part of the federal tax code’s progressivity just offsets regressive state and local tax codes, which tend to increase inequality, including racial disparities. Additionally, the U.S. raises less revenue as a share of GDP than most other OECD countries. Even a highly progressive tax system will do little to fund investments or reduce inequality directly if it raises relatively little revenue. So, a crucial way that the U.S. tax code could do more to reduce racial inequality would be to raise more revenue overall and do so progressively, with the revenue being used to fund investments that advance racial equity.

The second way the tax code affects racial disparities is its raft of tax breaks intended to help people succeed in the economy. Some are well designed to reduce racial disparities and should be boosted. But the bulk of them likely increase racial disparities and should be overhauled.

Effective and racially inclusive tax provisions like the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit reduce poverty and raise after-tax incomes of low- and moderate-income working families, and help children in these families have a better chance of being healthier, doing better in school, and earning more as adults. These tax credits serve more white households than any other racial or ethnic group (because there are more white households in the United States) but serve a larger proportion of people of color. They also serve a greater share of black, Latina, and Native American women. Boosting these credits – especially to allow them to better reach workers and families with the lowest incomes – would let them do more for households of color.

Many other tax provisions, such as the deduction for mortgage interest, go overwhelmingly to higher-income, disproportionately white households. These households least need help and would likely do what the tax break is meant to encourage even without the breaks. And these breaks can exacerbate racial income and wealth inequality and reinforce discrimination and other barriers that households of color face. Due to economic barriers influenced by racism, households of color often don’t benefit as much from tax breaks for income from wealth or owning a home, even when they have income and wealth similar to white households. Scaling back or overhauling tax breaks such as these would advance racial equity.

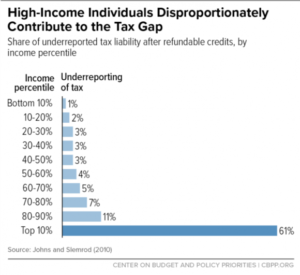

Third, tax administration can influence racial disparities. For example, deep cuts in IRS funding have led to a significant drop in audit rates for large corporations and high-income filers, who are overwhelmingly white. These taxpayers contribute disproportionately to the “tax gap” (taxes owed but not paid voluntarily on time). Audit rates among lower-income filers have not fallen as steeply — so higher-income, predominantly white geographies are facing lower audit rates than lower-income communities of color.

On the other hand, two IRS-sponsored programs seek to make tax administration more equitable and racially inclusive: Volunteer Income Tax Assistance, which provides free tax preparation to low-income filers, and Low-Income Taxpayer Clinics, which help low-income filers navigate disputes with the IRS. These programs help mitigate the unique language, cultural, and other challenges that communities of color may face in navigating tax filing and disputes.

Adequately funding these programs – and providing additional resources for tax enforcement to ensure the well-off pay what they owe in taxes — are examples of immediate ways to improve tax administration and advance racial equity.

Instead of using tax reform as an opportunity to increase equity, the 2017 tax reform increased racial disparities. Its core provisions tilt heavily towards households at the top: white households in the highest-earning 1 percent receive 23.7 percent of the law’s total tax cuts, far more than the 13.8 percentage share that the bottom 60 percent of households of all races receive. By contrast, the law generally treated low- and moderate-income households, disproportionately households of color, largely as an afterthought. For example, even as households with incomes as high as $400,000 received large Child Tax Credit increases, 11 million children under 17 in the lowest-income working families received either no improvement in the credit or a token increase. The 2017 law will also add $1.9 trillion to deficits over ten years at a time when the nation needs more revenue, not less, as the baby-boom generation moves deeper into retirement.

We need to chart a new direction rather than doubling down on these recent mistakes. Building off the suggestions here, policymakers should prioritize real tax reform that significantly bolsters the tax code’s role in reducing income, wealth, and especially racial disparities.

Chye-Ching Huang is Director of Federal Fiscal Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Roderick Taylor, formerly of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (where he conducted this research), is now a Research Analyst at the Urban Institute Justice Policy Center.