Mapping Our Child Care Deserts

Ask any parent of young children, and they’ll tell you that one of their biggest challenges is finding affordable, quality child care. The cost of child care alone is a barrier for many low-income and middle class families—for instance, a typical family may expect to pay $10,000 or more a year on a child care center. But research conducted by myself and colleagues at the Center for American Progress (CAP) shows that cost isn’t the only barrier families face in accessing child care: simply finding a child care program can be a struggle for many working families.

Our study examined the location of child care centers in eight states that together comprise 20 percent of the U.S. population under the age of five. We found that 42 percent of these young children live in “child care deserts”—defined as a ZIP code with more than three children for every child care center slot.

Child care deserts are a pervasive problem across the country. In the eight states included in the study, almost 2 million children under the age of five lived in a child care desert. In Minnesota, a full two-thirds of ZIP codes are child care deserts. Illinois also has a high proportion of child care deserts, with 60 percent of ZIP codes in the state considered deserts. Maryland and Georgia each had about one-third of ZIP codes that were child care deserts.

On the whole, rural areas are more likely to be deserts than suburban or urban areas. Of the regions we studied, 55 percent of children in rural areas live in a child care desert, compared to 36 percent of children in suburban areas and 49 percent of children in urban areas. But cities are not immune to limited child care supply: Chicago, for example, is the largest urban child care desert identified in the study, with five out of every six children under the age of five living in a desert.

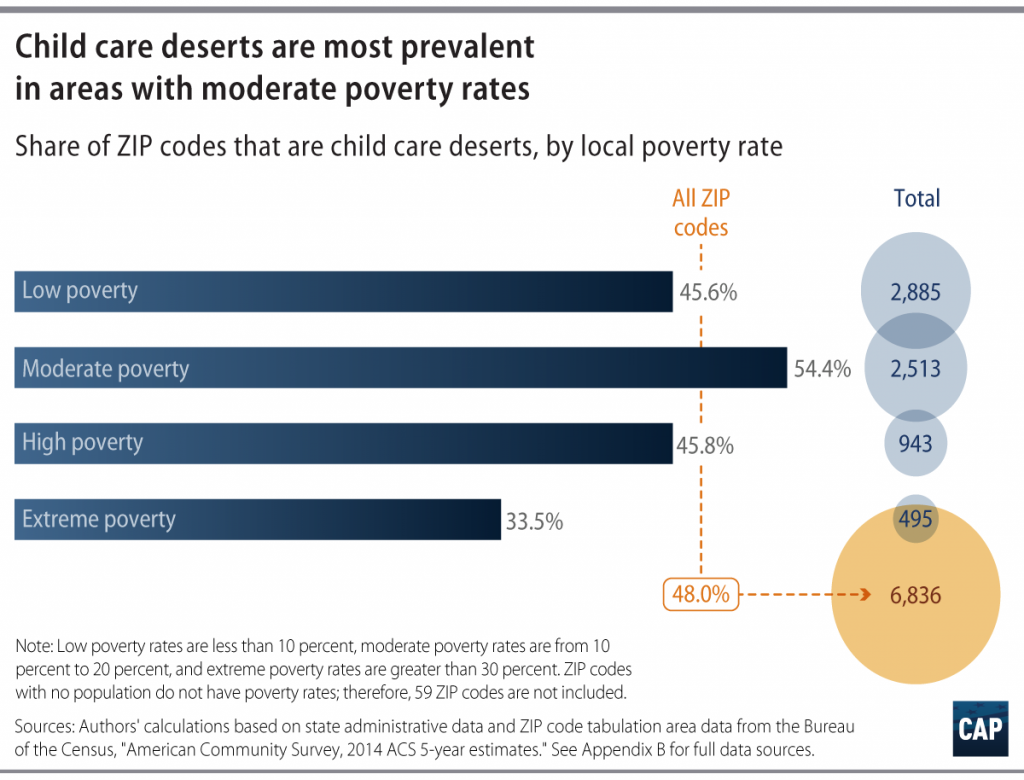

Communities with high poverty rates are not necessarily more likely to be child care deserts. In fact, areas with a poverty rate of 10 to 20 percent—slightly less than the national child poverty rate of 21 percent—were most likely to qualify as child care deserts.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise: in the 1960s, the federal government launched Project Head Start and built early childhood programs to serve poor children in communities across the country. In the last decade, many states have expanded preschool programs to prepare low-income children for school. While this research is far from conclusive, these preliminary results suggest that public funding for early childhood programs has been somewhat successful in building supply.

In the coming months, Head Start and federal child care funds will be the subject of debate, along with other programs serving low-income and middle class families. Politicians will question whether early childhood programs work and cite research on both sides of the debate.

But without public investments in early childhood programs, millions of poor children would be without any option. Already half of eligible four-year-old children do not receive Head Start, and only 5 percent of children under age three receive Early Head Start. And while Head Start programs provide much needed infrastructure in poor communities, many buildings are in dire need of repair.

At the same time, state preschool programs reach only about a quarter of four year olds, largely concentrated in states like Georgia and cities like New York City and Boston where public preschool is widely available. Programs for babies and toddlers are even more scarce: 65 percent of child care centers do not serve children under the age of one 1 and among programs that are available to parents at no cost, less than 10 percent serve children under a year.

For too long, we’ve viewed child care as a private family matter. But when families can’t find child care, they can’t work. And when parents have to settle for child care that doesn’t provide quality early learning opportunities, children can fall behind before they even start school. America’s child care problem threatens families’ financial security and the economic health of the country.

A national conversation about investing in child care and early education is past due. Just as the term “food deserts” led to a national conversation about access to healthy and affordable food in low-income neighborhoods, a robust discussion about child care deserts could provide the same opportunity for child care supply. As Congress considers an infrastructure investment to improve roads and bridges, we now have an opportunity to discuss economic supports for working families, starting with an infrastructure investment in preschool and child care.

Parents know that child care is vital to the fabric of our economy. It’s time that lawmakers recognize that with a sustained federal investment.

Katie Hamm is the Vice President for Early Childhood Policy at the Center for American Progress.

The views expressed in this commentary are those of the author or authors alone, and not those of Spotlight. Spotlight is a non-partisan initiative, and Spotlight’s commentary section includes diverse perspectives on poverty. If you have a question about a commentary, please don’t hesitate to contact us at commentary@spotlightonpoverty.org.

You can also sign up to receive our weekly newsletter and other updates here.