Hidden Hunger: Bobby Kennedy’s Illuminating Tour Through the Mississippi Delta

Fifty years ago this month, Senator and former Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, visited the Mississippi Delta as part of a Senate subcommittee review of War on Poverty on programs. In exploring this impoverished region, coming across empty kitchens and starving children, he discovered an unspoken epidemic of hunger that was devastating Mississippians. His visit would help bring this issue to the forefront, changing the landscape of hunger issues and poverty in the United States for years to come.

In her forthcoming book (to be released in Spring 2018) Delta Epiphany: RFK in Mississippi Ellen Meacham, journalist and instructor at the University of Mississippi, tells the story of Kennedy’s visit to the Mississippi Delta, exploring the history, economics, and politics of the region, and how those factors shaped the lives of the citizens of the area. Spotlight recently spoke with Meacham to discuss her forthcoming book and the 50th anniversary of Kennedy’s famous trip. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What brought Bobby Kennedy to the Mississippi Delta?

It was about two and a half years into the War on Poverty. Senator Bobby Kennedy was on the Senate Subcommittee on Employment, Labor, and Poverty, tasked with assessing President Johnson’s policies. In March 1967, the subcommittee hosted a series of hearings, where they discussed policies and programs enacted in both urban and rural areas. Marian Wright, a 27-year old NAACP lawyer and the first African American woman admitted to the Mississippi Bar testified before the committee on behalf of Head Start—a program that had nearly lost its funding. During the hearing, she went off topic and discussed the overwhelming poverty plaguing the South—and invited the senators to it see for themselves.

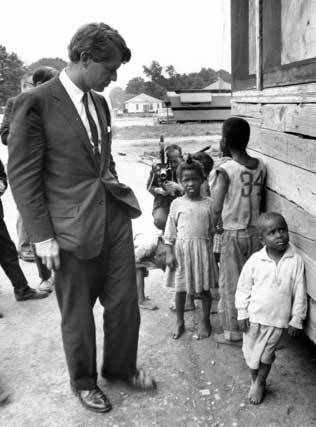

Photo by Dan Guravich

After the hearings concluded, the committee organized visits around the country, with the first stop in Mississippi. After a hearing in Jackson, the next day Kennedy and Senator Joseph Clark of Pennsylvania headed to the Mississippi Delta, where they met with activists and other locals working against the Jim Crow power structure in place.

What the senators encountered down there was a perfect storm: a combination of the mechanization of farming that was shifting some jobs to more skilled labor and killing others; federal agricultural subsidies that required some areas not to be farmed; and the institution of programs in Mississippi that required poor residents to buy food stamps (which of course they could not afford). And race existed as a backdrop for this, with white politicians worried about African Americans gaining political power and influence.

Hunger became widespread—thousands were affected. There was little to no infrastructure in place to protect the jobless, the homeless, and the hungry. Senator Kennedy was brought here by these issues. Today, people tend to remember it as a “poverty tour,” but he was actually there on a fact-finding mission.

What did Kennedy see on the visit?

He visited various programs, like Head Start, that received government funding as well as cities and villages that were severely affected by poverty While doing this, however, he purposely made some unscheduled stops, separate from his guide’s plans. He wanted to see more than what folks were just showing him.

In doing so, he found folks who had no source of income whatsoever. He met with a group of misplaced farm workers in Freedom City, a cooperative farm of sorts for displaced African American farm workers, talking to mothers and children who were going hungry. He saw folks in various stages of deprivation.

There’s this illuminating moment where he’s standing in a dark house, towering over a child who is listless and malnourished. He leans down, strokes the child’s face and tries to get a response from him with no success. As a father of ten (at the time), he was overcome with emotion, and after reluctantly walking away, wiped away tears.

What effect did the visit have on him personally? And what was the legacy for the country?

He was truly stunned by what he saw. He had seen this sort of poverty in other countries, but never saw it this bad in America. He was convinced that there wasn’t enough being done to help these people, and that was unacceptable. “If we can’t feed our children, what are we doing?”

He saw this poverty, this hunger, as an extension of the Civil Rights Movement. These suffering people had no power at the ballot box for generations, as they were subjected to Jim Crow laws, segregation, and discrimination. Sweeping legislation like the Voting Rights Act was still very new. They had no real political power to affect the kind of change they needed. He saw this issue as a unifying one—who would be against hungry children?

His trip received widespread national attention. In the wake of the visit, more communities in the region gradually began to receive both public and private aid. The press were now more directly aware of the hunger crisis throughout the United States. His trip truly brought hunger into the public discussion.

What is the region like today? What has changed and what hasn’t?

Political representation has changed. Mississippi now has the highest number of African American-elected officials in the United States. Compared to what Kennedy saw in 1967, there’s a lot more political representation and participation today. However, it has not necessarily translated into greater economic power and influence.

As for hunger, a lot of children he met didn’t receive food from the federal programs in place. Now, all public schools in the Delta have free and reduced lunch programs and other services. There are many more options in terms of food aid.

However, there’s still an enormous tangled knot of problems. This is still a very poor state that severely underfunds education and anti-poverty programs.

You also have a lot of rural areas emptying out and people moving into cities to find more opportunities. There are stll high rates of poverty and food insecurity, some of the highest in the nation. Some of the problems that the Delta has are not just unique to the region in that respect. There’s certainly still a lot more to be done.

Ellen Meacham teaches journalism at the University of Mississippi. Her book, Delta Epiphany: RFK in Mississippi, will be released in the spring of 2018.

The views expressed in this commentary are those of the author or authors alone, and not those of Spotlight. Spotlight is a non-partisan initiative, and Spotlight’s commentary section includes diverse perspectives on poverty. If you have a question about a commentary, please don’t hesitate to contact us at commentary@spotlightonpoverty.org. If you are interested in submitting a commentary for consideration, please review our guidelines here.

You can also sign up to receive our weekly newsletter and other updates here.